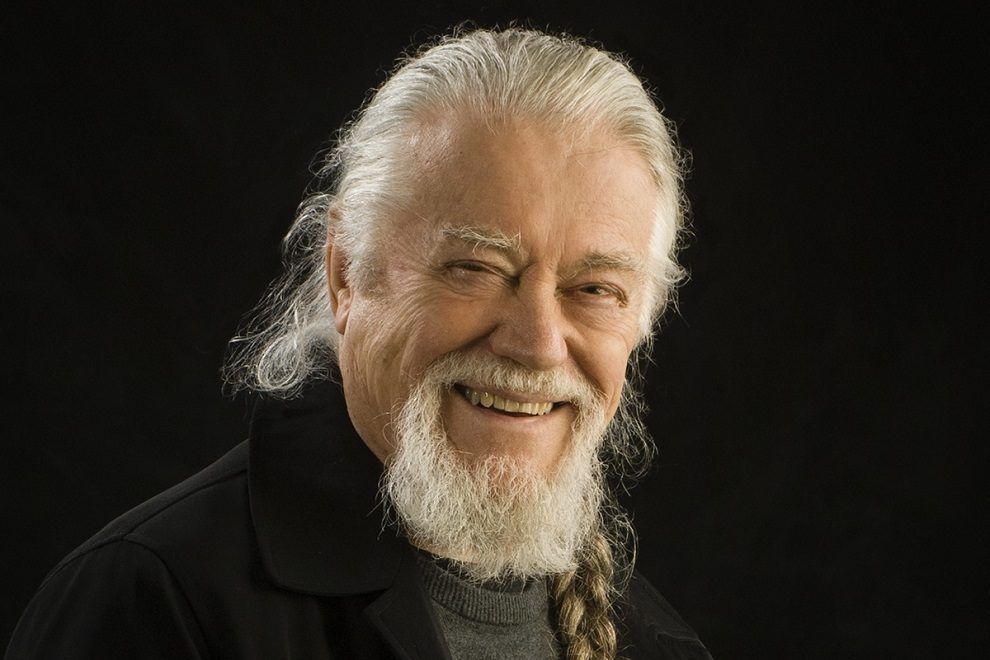

The prominent Canadian extradition law expert Gary Botting, based in Vancouver provides exclusive quotes and insights into the case during an interview with Khalid Athar, Chief Editor of Teletimes International

| Huawei’s CFO Ms. Meng Wanzhou is back in Canadian Courts for the final leg of a 2 plus years extradition case. There are many well-known Canadian Extradition lawyers keen to share their point of view on this case.

Gary Norman Arthur Botting is a prominent extradition law expert based in Vancouver. Gary’s Doctor Juris in Law (J.D./LL.B.) at University of Calgary was primarily in Criminal and Constitutional Law: thesis published as Fundamental Freedoms and Jehovah’s Witness. His Master’s degree in Law (LL.M.) at UBC (1999) was “Competing Imperatives: Individual Rights and International Obligations in Extradition from Canada to the U.S.A.” His Ph.D. in Law at UBC (2004) was “Executive and Judicial Discretion in Extradition between Canada and the United States.” Gary has published 12 books on extradition so far, including 5 editions of Canadian Extradition Law Practice (LexisNexis), three editions of Halsbury’s Laws of Canada: Extradition (LexisNexis), and two editions of Extradition between Canada and the United States (New York: Brill). His post-doctoral work was completed at University of Washington School of Law in Seattle in 2007. He has taught and been a research fellow or visiting scholar at University of Alberta, University of Calgary, Simon Fraser University, University of Washington, and UBC. Called to the B.C. Bar in 1991, he has been a practicing lawyer ever since. |

Teletimes: From a legal perspective, what are your general opinions about Ms. Meng Wanzhou case thus far?

Gary Botting: Generally speaking, the committal portion of the Meng case has been dragged out much too long. However, this strategy conforms to the unexpressed credo and modus operandi of extradition lawyers, used to inconvenience a “legal” process that is widely seen as being unconstitutional: “Delay, delay, delay!” This MO is fine if the individual being sought has endless resources, but of course doesn’t work for the average person, because both the person and the lawyer will end up in the poor house, without the resources to defend the actual trial once returned to the requested country. You can be sure that the lawyers in Canada will gear their defense to what their client can afford, leaving nothing in the bank; hence their clients are either lawyerless or at the mercy of public defenders when the need for legal representation is greatest—after the inevitable extradition. “Delay, delay, delay!” can only be justified, therefore, for the very well-heeled, or where it seems likely that the law is in flux and will change for the better.

As I have been saying since it was first presented as a Draft Bill in Parliament, the Canadian Extradition Act passed into law in 1999, is unconstitutional in its present form because it gives altogether too much discretion to the Minister of Justice and the International Assistance Group of the Department of Justice, and because it shackles and gags the committal judges by confining their role to whether the person before them is indeed the accused (a no-brainer) and whether his or her alleged conduct is criminal in Canada. The only other concern of the judge is whether the extradition partner or the Canadian authorities have committed an unconstitutional act so egregious that it directly impacts on the fairness of the committal hearing itself – a very narrow window of opportunity.

Given the clearly limited role of the extradition judge, the International Assistance Group usually books a single day for the entire extradition hearing, so that it presents its case in the morning, and the defence can voice any objections in the afternoon. Judgment is usually reserved, because every decision becomes a precedent for every case that follows, and is subject to appeal. The average criminal lawyer new to extradition will go along with this schedule, which of course will result in committal every time. More seasoned lawyers book at least two days and warn the court that the hearing might take longer for constitutional reasons, usually (at that point) unspecified. I usually book a week to cover all eventualities. Multiply that by the number of co-accused, and you have a ball-park figure of how long the initial hearing will usually take.

Sounds arbitrary? It is, but no more than the law itself, as written: All the cards are in the Justice Department deck, and they deal the person most in jeopardy a deuce. This is the consistent modus operandi of the International Assistance Group. It is designed so that international “comity” (i.e. toadying to other nations) defeats common sense (i.e. compassion and reasonableness).

Having said that, what are my opinions about the Ms. Meng case so far?

a) The provisional warrant should not have been issued in the first place, and certainly should not have been converted to an extradition warrant two months later on the skimpy evidence provided by the U.S. Department of Justice;

b) The Prime Minister and Minister of Justice have been ill-advised from the outset by the peons in the upper echelons of the International Assistance Group, all of whom suffer from tunnel vision in that they obsessively seek to kowtow to the requesting state; the United States (for example) says “Jump!” and, ever so startled, the Canadian Department of Justice replies, “How high?”

c) The Minister of Justice has demonstrated appalling weakness of character in not simply ordering the discharge of Ms. Meng, given that it is entirely within his purview to do so under section 23 of the Act;

d) The Prime Minister and Minister of Justice were wrong in their saying that for them to interfere in the process would be a violation of the Rule of Law-since the law allows precisely for that eventuality, and when they uttered those (apparently indelible) words, the case was not before the courts; in any case, the court’s role is merely advisory, and the surrender decision is entirely that of the Minister.

e) The prescribed role of the judiciary is strictly to determine whether the conduct of Ms. Meng would be criminal in Canada—including whether Canada would have jurisdiction to prosecute her given the existential situation of Canada having acquiesced to some sanctions against Iran (the answer to this seeming conundrum is obvious: Canada would not prosecute—or it would have already!);

f) The two-year timeline, while not sanctioned by the Act, is predictable, given the extradition lawyer’s unwritten credo (“Delay, delay, delay!”) to defeat the unimaginable harm caused by a lop-sided piece of legislation drafted by the Department of Justice specifically to meet their pragmatic goals without consideration of human or constitutional rights beyond the most discursive and dismissive sense (for example, the main individual rights and protections set out in sections 46 and 47 of the Act are nullified by section 45 where a treaty is in place;

g) It has been predictable that the committal judge has decided nothing of consequence so far, because that is her job—to do nothing but order committal on the stringent grounds provided by law. Even if she discharges Ms. Meng at this point, the Department of Justice can (and probably will) appeal.

TT: Have you seen any inconsistencies or inaccuracies in the evidence from the prosecution so far?

GB: Any inconsistencies that I have seen involve U.S. policy and jurisdiction. The United States is not an international police force: far from it! It winks at its own executives making deals worth billions of dollars, including Trump and his ilk, yet arrests Ms. Meng as CFO of a Chinese corporation for alleged conduct that is said to have occurred in Hong Kong with a bank registered in the UK? On the basis that the transaction, had it been completed, would have been in U.S. dollars cleared through a New York clearinghouse? Give me a break! (And while you’re at it, give Ms. Meng a break too!)

TT: Now until May will be critical for the case. Compared to the beginning of the case, can recent developments in the arrest process of Ms. Meng give rise to new factors that affect the trial?

GB: As I have said before, the police and CBSA tapes are reminiscent of the old Keystone Kops silent movies. They all but wet themselves with excitement. It’s like a trout fisherman who hooks a turbot and doesn’t know how to land it. (Tip: you don’t try. You cut it free!)

TT: Given the different branches that Ms. Meng’s lawyers have been fighting for, how solid is the justification of Canadian authorities to arrest Meng?

GB: This is a bifurcated question, so I’ll give a bifurcated answer.

a. There is no doubt that Canadian authorities had the right to arrest Ms. Meng on a provisional warrant, given the provisions of the Act and the Treaty. But obviously, the provisions surrounding provisional warrants must be reexamined, if they can be exercised so sloppily. Once the U.S. DOJ told the Canadian DOJ that a suspected felon was entering Canada, that’s all it takes. The U.S. then has two months to perfect its application for extradition, including presenting a record of the case outlining the evidence. In other words, Canada can arbitrarily detain anyone any treaty partner requests, pending formal allegations; there is absolutely no doubt that Ms. Meng’s arrest and detention were arbitrary, even though it accorded with the law. Here, the law is the ass.

b. But so were the authorities in trying to enforce that law. This “big fish” situation probably hadn’t arisen before. They were so anxious not to blow it that they blew it! They could have calmly explained to Ms. Meng that there was a provisional warrant for her arrest, and she would have to wait for the appropriate authorities to arrive to execute it. End of story. As it was, there is at least an appearance of abuse of process surrounding her actual arrest and detention—probably not serious enough to justify remedy by discharging her. There are many instances of more egregious detentions that have been ruled constitutional. As for breaching of international law, this issue is not germane to what Canada has done so much as what the United States has done in abusing the extradition treaty system to arrest an individual in order to curb the actions of a successful rival corporation. Canada is complicit in this only because its officials have been too blinded by the brightness of American hegemonic aspirations in North America to appreciate that we are unwitting victims to what is really a dispute between China and the United States.

TT: The defense and the prosecution just finished the submissions on the first branch of abuse of process. Did you have any particular opinions on what was presented there?

GB: Bungling incompetence in unusual circumstances is understandable and therefore to a degree excusable (see the allusion to the Keystone Kops above). So this is not likely to rise to the level of a abuse of process worthy of discharge. Nor will Trump’s blathering: Trump is, was and always will be an irrelevance.

TT: It is believed that under the previous administration, the US sought to use the extradition proceedings against Ms. Meng for political and economic gain. Do you personally think that argument holds weight based on what you’ve seen?

GB: Ditto. Trump’s blathering, as the judge plainly sees, is not even worthy of a footnote: he is at best an “end” note. However, that is not to say that the United States has not been motivated by political and economic advantage. In fact this, in my view, has been the motivating factor from the outset. The United States simply does not have jurisdiction to prosecute a corporate executive for a decision made or actions conducted outside its jurisdiction.

Huawei was and is a political target. The arrest of Ms. Meng on 1 December 2018 stuck a knife in the belly of Huawei at the very moment she was on her way to promote Huawei’s 5G Technology to Mexico: Mexico City would have been a perfect venue for a major expansion of 5G. An appealing personality and consummate promoter of a product in which she believes, she would have enthralled her Mexican audience and they would in all likelihood of gone with Huawei. The way I see it, the United States blatantly enlisted Canada’s aid to thwart any attempt by Huawei to expand and extend its technology into North America. This is an example of U.S. hegemony writ large.

TT: Will the fact that the present U.S. administration is now in charge influence the outcome of the case, in your opinion?

GB: The only way to level the playing field and bring justice back to Ms. Meng is for the United States to drop the charges against her—in other words, to strike her name from the indictment. It could be that the new Attorney General could order a review of the indictment and decide that the U.S. does not have jurisdiction after all. It could be that the prosecutor himself or herself sees that they cannot ultimately win. It could be that the current anti-Asian sentiment in the United States is a factor that the U.S. is prepared to deal with, comprehending that Ms. Meng cannot possibly get a fair trial (or even safe custody) in the United States.

Bottom line: her name must be removed from the U.S. indictment, no strings attached. At that point, Canada would immediately discharge her and she could go home to China or stay in Canada, in accordance with her existing travel documents.

If she is discharged by the Canadian court, the Department of Justice has the right to appeal. If it chooses not to appeal, she has the right to go back to China. However, as long as the U.S. indictment is still in place, wherever she goes in the world—including Canada—she can be rearrested on a provisional warrant, and the whole process can begin again. So says our flawed law—and most treaties.

If she is committed for extradition by the Canadian court (the most likely outcome), her lawyers have 30 days to do two things a) file an appeal; and b) make submissions to the Minister of Justice as to why she should not be surrendered for extradition. The submissions may include humanitarian grounds (e.g. Asian women are arbitrarily targeted in the U.S. and therefore cannot be kept safe, especially within the prison system), arguments that the charges or the motivation for bringing them are political (the most likely to succeed, in my opinion), or jurisdictional grounds (however, the Minister will usually say that that was the domain of the extradition judge; committal will automatically imply that jurisdiction is not an issue since it has already been decided that the offence would amount to a crime in Canada – a classic case of Catch-22). The Minister of Justice can either order her surrender or order her discharge. At this point (or at any point along the way so far—it’s entirely up to the Minister’s discretion under section 23), the Minister’s order to discharge her is not appealable. However, his order to surrender is subject to judicial review, which is heard by the provincial Court of Appeal at the same time as the appeal of committal—probably a year or two down the road. That decision is appealable to the Supreme Court of Canada only where the three justices do not agree. Although the appellant can seek leave to appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada despite unanimity of opinion, leave is rarely if ever given. If leave to appeal is ordered, add another year.